The other monolithic figure of early modern banking was the House of Morgan. Led by the notorious J.P. Morgan (junior and senior), the Morgan bank stood atop the international financial world for over a century, controlling railroads, telegraph networks, mining concerns, shipping lines, lumber, oil and steel conglomerates and greatly influencing the politics of four continents. At its height, the House of Morgan simultaneously symbolized all that is good and bad about American capitalism. J.P. Morgan was an original patron of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gave generously to the American Museum of Natural History and St. Luke’s Hospital, kept a seldom-occupied box at the Metropolitan Opera and helped launch the legendary Groton prep school. At the same time, his bank loaned money to fascist Italy, bankrolled Mussolini’s American P.R. campaign and financed wars on at least three continents.

Morgan, along with the other influential banks of the day, National City Bank, Kuhn Loeb and Co., and Brown Bros. Harriman, ushered in the era of globalism that now dominates international trade; and their “gentleman Banker’s Code” would be considered insider trading by today’s standards. Nevertheless, for good or ill, the House of Morgan was instrumental in America’s rise to its present position as the world’s lone superpower.

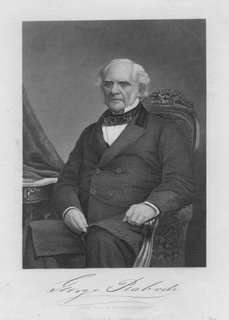

Like the Rothschilds before it, the House of Morgan has humble beginnings. Originally called the House of Peabody, the bank was founded by a rags-to-riches Baltimore dry-goods merchant named George Peabody. Peabody dropped out of school when his father died and went to work in his brother’s shop to support his widowed mother and six siblings. His flair for business gained him the capital to move to Baltimore and buy into a partnership with successful merchant Elisha Riggs, whom he met while fighting in the War of 1812. Together, Peabody and Riggs worked their way to the top of Baltimore’s merchant class.

In 1835, like most of the other former British colonies, Maryland was saddled with debt. They had taken out loans from London banks to finance railroads and canals, which they hoped would spur business and foster trade. When the new commerce failed to materialize, Maryland, like several other states, found herself in a financial pickle. Local hatred toward foreign bankers caused state legislatures to threaten to renege on the loans, and Peabody was selected to lead a commission to renegotiate the debt. Peabody successfully argued that only more loans would assure repayment of the old ones, and secured an additional $8 million for Maryland.

While in London, Peabody fell in love with the business and lifestyles of the city’s merchant bankers, and he decided to move there and form his own bank. In 1837, with a loan from Riggs, he did just that, setting up Peabody, Riggs and Co. at the prestigious address of 31 Moorgate in London. Now he was shoulder-to-shoulder with such banking luminaries as the Baring Brothers, who had financed the Louisiana Purchase, and the aforementioned Rothschilds.

But it was an uphill battle for Peabody in this new enterprise. State after state reneged on interest payments, and five American governors formed a debtor’s cartel leveraging for debt repudiations. Peabody’s partner, Riggs, wanted out of the arrangement, and Peabody was forced to go it alone. Moreover, entry into the celebrated society of British bankers – already difficult for an American – became impossible under the cloud of defaulted American loans.

But Peabody’s neighbor, the Barings Bank, was also stuck with defaulted bond issues, and together the two houses concocted a scheme to get the states back on good footing. The plot involved such shameless acts as paying newspapers to run editorials in favor of debt repayment, establishing a political slush fund to be used for electing (mostly Whig) pro-debt repayment legislators and even convincing clergymen to preach on the moral sanctity of contracts. They even bribed the orator and statesman Daniel Webster to make speeches on the topic.

The ploy worked. With a couple of exceptions, the depreciated state bonds that Peabody had bought up resumed interest payments, and Peabody reaped a fortune. Later, with revolution in Europe, a gold rush in California and a war with Mexico, American securities became the safe bet and the House of Peabody’s standing among the London merchant bankers was cemented.

Though known for his philanthropy later in his life, Peabody was friendless miser. “I have never forgotten and never can forget the great privations of my early years,” he once told an acquaintance. This scar upon his memory greatly affected his attitude toward money, and some have observed that the philanthropy for which he is remembered today was little more than an attempt to repair his reputation as a tightfisted loner.

Junius Morgan, who had become Peabody’s partner in 1854, later recounted an episode that perfectly illustrates Peabody’s stinginess. Upon arriving to work one morning, Morgan found Peabody at his desk looking pale and feverish. “Mr. Peabody, with that cold you ought not to stick here,” Morgan suggested. Peabody reluctantly agreed and proceeded home. Twenty minutes later, while on his way to the Royal Exchange, Morgan came upon Peabody standing in the driving rain. “I thought you were going home,” exclaimed Morgan. “Well I am, Morgan,” Peabody replied. “But there’s only been a two-penny bus come along as yet and I am waiting for a penny one.”

Peabody’s Parsimony extended to other matters, as well. In 1854, when Junius Spencer Morgan became Peabody’s only partner, part of the agreement was that in ten years’ time, Peabody would leave the reins – and the firm’s name – to Morgan. After nearly 30 years of work, the House of Peabody had become one of the pillars of international finance; continuing the name would help assure continued success. But in 1864, even as he was donating thousands to charities all over the world, he refused Morgan use of the Peabody name.

“It was, at that time, the bitterest disappointment of [his] life that Peabody refused to allow the old firm name to be continued,” Morgan’s grandson recalled. Morgan reluctantly changed the name to J.S. Morgan and Company.

Despite Peabody’s stinginess in personal matters, he was generous in his endowments to a wide variety of charities. He formed a trust fund to build housing for London’s poor. Called Peabody Estates, they had gas lamps and running water, unlike the fetid hovels that had hitherto served as the city’s poorhouses. The trust fund continues today, financing subsidized housing in London. He endowed a natural history museum at Yale, an archeology and ethnology museum at Harvard and an educational fund for emancipated southern blacks. Each of these gifts bore the Peabody name, which is why he is remembered even today for his philanthropy.

“Unlike later Morgan benefactions, often anonymous and discreet,” notes The House of Morgan author, Ron Chernow, “Peabody wanted his name plastered on every library, fund, or museum he endowed.” Unfortunately for Morgan, this did not extend to his banking house. “Perhaps in his new sanctity,” Chernow adds, “he wanted to erase his name from the financial map and enshrine it in the world of good works.”

When Peabody died in 1869, the British government prepared a grave for him at Westminster Abbey in an effort to recognize his generous endowment to London’s poor. But Peabody’s wish was to be buried in his birthplace, Danvers, Massachusetts. So, Queen Victoria arranged for his body to be transported stateside upon The Monarch, England’s newest and most formidable warship.

In 1946, Thomas Lamont, chairman of J.P. Morgan and Co., asked Lord Bicester, senior partner of Morgan Grenfell, the London branch of the bank, for a copy of Queen Victoria’s letter thanking Peabody for aiding London’s poor. Bicester replied in part:

“I have always understood that Mr. Peabody, though known as a great philanthropist, was one of the meanest men that ever walked…I believe he left several illegitimate children unprovided for.”

Check back later for more on J.P. Morgan and Co.

Tuesday, November 8, 2005

The Trickle-Up Theory (part 3)

Posted by creation of the nation at 7:55 AM

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment