Monday, November 17, 2008

Finanzeinsturz

Posted by creation of the nation at 10:13 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, irrational murderous rage, rancorous humor, social justice

Saturday, March 29, 2008

Ten Days That Changed Capitalism

David Wessel

The past 10 days will be remembered as the time the U.S. government discarded a half-century of rules to save American financial capitalism from collapse.

On the Richter scale of government activism, the government's recent actions don't (yet) register at FDR levels. They are shrouded in technicalities and buried in a pile of new acronyms.

But something big just happened. It happened without an explicit vote by Congress. And, though the Treasury hasn't cut any checks for housing or Wall Street rescues, billions of dollars of taxpayer money were put at risk. A Republican administration, not eager to be viewed as the second coming of the Hoover administration, showed it no longer believes the market can sort out the mess.

"The Government of Last Resort is working with the Lender of Last Resort to shore up the housing and credit markets to avoid Great Depression II," economist Ed Yardeni wrote to clients.

First, over St. Patrick's Day weekend, the Fed (aka the Lender of Last Resort) and the Treasury forced the sale of Bear Stearns, the fifth-largest U.S. investment bank, to J.P. Morgan Chase at a price so low that a shareholder rebellion prompted J.P. Morgan to raise the price. To induce J.P. Morgan to do the deal, the Fed agreed to take losses or gains, if any, on up to $29 billion of securities in Bear Stearns's portfolio. The outcome will influence the sum the Fed turns over to the Treasury, so this is taxpayer money; that's why the Fed sought Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson's OK.

Then the Fed lent directly to Wall Street securities firms for the first time. Until now, the Fed has lent directly only to Main Street banks, those that take deposits from ordinary folks. That's because banks were viewed as playing a unique economic role and, supposedly, were more closely regulated than other types of lenders. In the first three days of this new era, securities firms borrowed an average of $31.3 billion a day from the Fed. That's not small change, and it's why Mr. Paulson, after the fact, is endorsing changes to give the Fed more access to these firms' books.

Increased Leverage

In the days that followed, the Republican Treasury secretary leaned on two shareholder-owned, though government-chartered, companies -- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac -- to raise capital that their boards didn't want to raise. In exchange, their government regulator allowed them to increase their leverage so they can buy about $200 billion more in mortgage-backed securities.

So Fannie and Freddie will get bigger, a welcome development when mortgage markets are in trouble. Already, they have regained lost market share. They accounted for 76% of new mortgages in the fourth quarter of last year, up from 46% in the second quarter, Mr. Paulson said Wednesday. But everyone knows that if Fannie or Freddie stumble, taxpayers will get stuck with the tab.

And then, the federal regulator of the low-profile Federal Home Loan Banks, which are even less well capitalized than Fannie and Freddie, said they could buy twice as many Fannie and Freddie-blessed mortgage-backed securities as previously permitted -- more than $100 billion worth.

Was this necessary? It's messy, uncomfortable and undoubtedly flawed in many details. Like firefighters rushing to a five-alarm fire, policy makers are making mistakes that will be apparent only in retrospect.

Too Great to IgnoreBut, regardless of how we got here, the clear and present danger that the virus in the housing, mortgage and credit markets is infecting the overall economy is too great to ignore. The Great Depression was worsened because the initial government reaction was wrong-headed. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke spent an academic career learning how to avoid repeating those mistakes.

Is it working? It is helping. One key measure is the gap between interest rates on mortgages and safe Treasury securities. A wide gap means high mortgage rates, which hurt an already sickly housing market. A lot of recent activity, including Wednesday's previously planned auction in which the Fed is trading Treasurys for mortgage-backed securities, is aimed at increasing demand for those securities to drive down mortgage rates.

The gap remains enormous by historical standards, but has narrowed. On March 6, according to FTN Financial, 30-year fixed-rate mortgages were trading at 2.92 percentage points above the relevant Treasury rates; Wednesday the gap was down to 2.22. Normal is about 1.5 percentage points. Money markets are still under stress, as banks and others hoard cash and super-safe short-term Treasurys.

Is it enough? Probably not. Although it's hard to know, the downward tug on the overall economy from falling house prices persists. The next step, if one proves necessary, is almost sure to require the explicit use of taxpayer money.

Cushion the Blow

The case for doing more is twofold. One is to cushion the blow to families and communities, even if some are culpable. The other is to disrupt a dangerous downward spiral in which falling prices of houses and mortgage-backed securities lead lenders to pull back, hurting the economy and dragging asset prices down further, and so on.

In ordinary times, a capitalist economy lets prices -- such as those of homes, mortgage-backed securities and stocks -- fall to the point where the big-bucks crowd rushes in, hoping to make a killing. But if the big money remains on the sidelines, unpersuaded that a bottom is near, the wait for bargain hunters to take the plunge could be very long and very painful.So the next step, no matter how it is dressed up, is likely to involve the government's moving in ways that put a floor under prices, hoping that will limit the downside risks enough so more Americans are willing to buy homes and deeper-pocketed investors are willing, in effect, to lend them the money to do so.

Posted by creation of the nation at 8:42 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, bureaucrats, incompetence, WALL STREET

Friday, January 4, 2008

Bullies, Muggers, Thieves & Con Men

The beginning of political wisdom is the realization that despite everything you’ve always been taught, the government is not really on your side; indeed, it is out to get you.

Sometimes government functionaries and their private-sector supporters want simply to bully you, to dictate what you must do and what you must not do, regardless of whether anybody benefits from your compliance with these senseless, malicious directives. The drug laws are the best current example, among many others, of the government as bully. Our rulers presently enforce a host of laws that combine the worst aspects of puritanical priggishness and the invasive, pseudo-scientific, therapeutic state. They tolerate our pursuit of happiness only so long as we pursue it exclusively in officially approved ways: gin, yes; weed, no.

Notwithstanding the great delight that our rulers take in tormenting us with their absurdly inconsistent nanny-state commands, they generally have bigger fish to fry. Above all, the government and its special-interest backers want to take our money. If these people ran a store, they might aptly call it Robberies R Us. Their credo is simple and brazen: “you have money, and we want it.”

Unlike the sincere street criminal, however, the robber in official guise rarely puts his proposition to you in the blunt form of “your money or your life,” however much he intends to relate to you on precisely such terms. (If you doubt my characterization of these intentions, test what happens if you steadfastly resist at every step as the brigands escalate their threats: first ordering you to pay, then billing you for unpaid balances plus penalties and interest, sending you a summons, and ultimately beating you into submission or killing you for resisting arrest. Your sustained, open resistance always ends in the state’s use of violence against you, in either your forcible imprisonment or your removal from the land of the living, after which your memory will be defamed by your designation as a criminal—governments never settle for mere brutality, but always supplement it with unabashed presumptuousness.)

When I say “rarely,” I do not mean that the authorities never carry out their plunder blatantly. Throughout the land, for example, criminal courts, acting as de facto muggers, strip people of great sums of money in the aggregate by fining them for conduct that ought never to have been criminalized in the first place—drug-law violations, prostitution, gambling, antitrust-law violations, traffic infractions, reporting violations, doing business without a license, and innumerable other victimless “crimes.” The predatory judges and their police henchmen care no more about justice than I care to live on a diet of pig pancreas and boiled dandelions. They are simply taking people’s money because it’s there to be taken with minimal effort. In this manifestation, government amounts to a gigantic speed trap.

The more common way for government officials to rob you, however, involves their seizure of so-called taxes, which take countless forms, all of which are purported to be collected in order to finance—mirabile dictu—benefits for you. Such a deal! You’d have to be a real ingrate to complain about the government’s snatching your money for the express purpose of making your world a better place.

Sometimes the “political exchange” into which you are hauled kicking and screaming rests on such a ludicrous foundation, however, that honesty compels us to classify it, too, as a mugging. I have in mind such compassionately conservative policies as stripping taxpayers of hundreds of billions of dollars and handing the money over, for the most part, to rich people engaged in large-scale agribusiness and, sometimes, to landowners who don’t even bother to represent themselves as farmers. The apologies that the agribusiness whores in Congress make for this daylight robbery are so patently stupid and immoral that the whole shameless affair resembles nothing so much as the schoolyard bully’s grabbing the little kids’ lunch money and then taunting them aggressively, “If you don’t like it, why don’t you do something about it?” Every five years, when the farm-subsidy law expires and a new one is enacted, a few members of Congress pose as reformers of this piracy, but truly serious reforms never occur, and even the minor ones that come along from time to time prove unavailing, as the farm-booty interests invariably suck up “emergency relief” payments from the public treasury later on to make up for any shortfalls from the main subsidy programs.

Government sneak thieves, in contrast, fear that they may occupy more vulnerable positions than the agribusiness gang and similarly impudent special-interest groups cum legislators, so they dare not taunt the little kids so flagrantly. Instead, they specialize in legislative riders, budgetary add-ons and earmarks, logrolling, omnibus “Christmas tree” bills, and other gimmicks designed to conceal the size, the beneficiaries, and sometimes even the existence of their theft. At the end of the day, the taxpayers find there’s nothing left in the till, but they have little or no idea where all of their money went. Finding out by reading an appropriations act is next to impossible, inasmuch as these statutes are almost incomprehensible to everyone but the legislative insiders and their staff members who devise them and write them down in a combination of Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit.

For example, for many years, a single congressman from northeastern Pennsylvania—first Dan Flood and then Joe McDade—substantially enriched the anthracite coal interests of that region by inserting a brief, one-paragraph limitation rider in the annual appropriations act for the Department of Defense. The upshot of this obscure provision was that Pennsylvania anthracite was transported to Germany to provide heating fuel for U.S. military bases that could have been heated more cheaply by using local resources. This coals-to-Newcastle shenanigan was a classic sneak-thief gambit, a thing of legislative beauty, but every year’s budget contains thousands of schemes that operate with similar effect, if not in an equally audacious manner.

Unlike the government sneak thieves, the government con men openly advertise—indeed, expect to receive great credit for—certain uses of the taxpayers’ money that are represented as bringing great benefits to the general public or a substantial segment of it. Surely the best example of the con man’s art is so-called national defense, a bottomless pit into which the government now dumps, in various forms (many of them not officially classified as “defense”), approximately a trillion dollars of the taxpayers’ money each year. The government stoutly maintains, of course, that all ordinary Americans are constantly in grave danger of attack by foreigners—nowadays, by Islamic terrorists, in particular—and that these voracious wolves can be kept from the door only by the maintenance and active deployment of large armed forces equipped with ultra-sophisticated (and correspondingly expensive) equipment and stationed at bases in more than a hundred countries and on ships at sea around the globe.

Without dismissing the alleged dangers entirely, a sensible person quickly appreciates that the threat is slight—just do the math, using reasonable probability coefficients—whereas the cost of (purportedly) dealing with it is colossal. In short, as General Smedley Butler informed us more than seventy years ago, the modern military establishment, along with most of its blessed wars, is for the most part nothing but a racket. Worse, because of the way it engages and co-opts powerful elements of the private sector, it gives rise to a costly and dangerous form of military-economic fascism. Lately, the classic military-industrial-congressional complex has been supplemented by an even more menacing (to our liberties) security-industrial-congressional complex, whose aim is to enrich its participants by equipping the government for more effectively spying on us and invading our privacy in ways great and small.

Worst of all, despite everything that is claimed for the military’s protective powers, its operation and deployment overseas leave us ordinary Americans facing greater, not lesser, risk than we would otherwise face, because of the many enemies it cultivates who would have left us alone, if the U.S. military had only left them alone. (Yes, Virginia, they are over here because we’re over there.) The president routinely declares that the hugely increased expenditures and overseas deployments for military purposes since 2001 have reduced the threat of terrorism, but, in fact, terrorist incidents and deaths have increased, not decreased. Although privileged elements of the political class gain from militarism and neo-imperialist wars, the rest of us invariably lose economic well-being, real security, and all too often life itself. In 2004, people who said that security against terrorism was their top concern voted disproportionately, by an almost 7-to-1 margin, for George W. Bush. They had been conned.

Although the mugger, the sneak thief, and the con man are not the only types of government operatives, they make up a large proportion of the leading figures in government today. The lower ranks, especially in the various police agencies, have a disproportionate share of the bullies. No attempt to understand government can succeed without a clear understanding of these ideal types and each one’s characteristic modus operandi. With this understanding firmly in mind, you will remain permanently immune to the infectious swindle, “I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.” The truth, of course, is the exact opposite: I say again, the government—this vile assemblage of bullies, muggers, sneak thieves, and con men—is not really on your side; indeed, it is out to get you.

Posted by creation of the nation at 7:51 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, bureaucrats, irrational murderous rage, psychotic leaders, public realm

Tuesday, February 27, 2007

Trickle Up Economics

Frequent readers of BDM (all six of you), have probably encountered a term I think I coined: the Trickle Up Theory.

As you have probably guessed, "Trickle Up Theory" is my somewhat snotty response to the Trickle Down Theory of economics, which seems to rear its ugly head at least once per decade. The Reaganites called it Reganomics, natch; the Clintonites called it “supply-side” economics. Not sure what Bush Inc. is calling it, “nukuler smok-em-out” economics, probably.

Of course, supply-side economics doesn’t work. Cutting taxes for these guys doesn’t spur economic growth. Nor does it create jobs, increase wages or generate income, as its proponents would have you believe. All it does is make these guys richer. And their mistresses too.

And where does all that money come from? From us. That’s why I call it the Trickle Up Theory. Money trickles up from us po’ folk to the rich. Get it? There are lots of mechanisms in place to facilitate this poor-to-rich trickle—insurance companies, temp agencies, banks, governments, debt collectors—so much so that it’s actually a stream. Perhaps even a torrent.

Here’s a good example of locally grown (groan) Trickle Up Economics. Here’s the global variety.

Anyhoo.

Another thing I’ve noticed about Trickle Up Economics is that as money trickles up to the rich, accounting prowess trickles down to the poor. That is, the most fastidiously accurate accountants seem to be hanging around us lowly wage earners, while the really incompetent accountants seem to be working for huge government agencies and global investment firms and multi-billion-dollar military contractors and stuff. Life is full of ironies, I guess.

Take the Pentagon, for example. According to some estimates, the Pentagon has lost $2.3 trillion. That’s right—trillion.

Dollars.

Lost.

That’s roughly $8,000 per American. Meanwhile, the U.S. Dept. of Education is after me for the $800 I still owe on my student loans. I’ll tell you what, Dept. of Education, as soon as the Pentagon finds the $2.3 trillion, I’ll cough up the $800 out of my share. How’ll that be? Super.

I have a letter from Xcel Energy magneted to my fridge. Xcel Energy is the multi-state energy company once headed by former Energy Secretary Hazel O’Leary back when it was known as Northern States Power. After O’Leary’s four scandal-plagued years with the Clinton regime, NSP wisely changed its name.

But back to the letter. The letter from Xcel Energy was sent to inform me that there was one cent left over from the account at my previous apartment, and that they are transferring said amount to the account at my new address. Once cent. Now that’s efficiency!

Hey! I’ve got an idea! Let’s take all the Xcel Energy accountants and trade them to the Pentagon. The Pentagon accountants can then work for Xcel. I mean, a penny here or there doesn’t really matter that much. I’m confident that Xcel can make up the difference from the occasional missing penny. But the Pentagon clearly needs help.

Well, that was easy. (yawn) Maybe tomorrow I’ll tackle NASA.

Posted by creation of the nation at 9:50 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory

Tuesday, November 8, 2005

The Trickle-Up Theory (part 3)

The other monolithic figure of early modern banking was the House of Morgan. Led by the notorious J.P. Morgan (junior and senior), the Morgan bank stood atop the international financial world for over a century, controlling railroads, telegraph networks, mining concerns, shipping lines, lumber, oil and steel conglomerates and greatly influencing the politics of four continents. At its height, the House of Morgan simultaneously symbolized all that is good and bad about American capitalism. J.P. Morgan was an original patron of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gave generously to the American Museum of Natural History and St. Luke’s Hospital, kept a seldom-occupied box at the Metropolitan Opera and helped launch the legendary Groton prep school. At the same time, his bank loaned money to fascist Italy, bankrolled Mussolini’s American P.R. campaign and financed wars on at least three continents.

Morgan, along with the other influential banks of the day, National City Bank, Kuhn Loeb and Co., and Brown Bros. Harriman, ushered in the era of globalism that now dominates international trade; and their “gentleman Banker’s Code” would be considered insider trading by today’s standards. Nevertheless, for good or ill, the House of Morgan was instrumental in America’s rise to its present position as the world’s lone superpower.

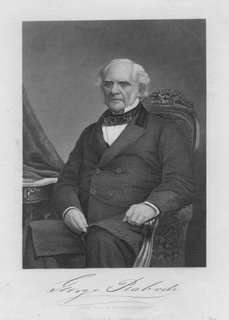

Like the Rothschilds before it, the House of Morgan has humble beginnings. Originally called the House of Peabody, the bank was founded by a rags-to-riches Baltimore dry-goods merchant named George Peabody. Peabody dropped out of school when his father died and went to work in his brother’s shop to support his widowed mother and six siblings. His flair for business gained him the capital to move to Baltimore and buy into a partnership with successful merchant Elisha Riggs, whom he met while fighting in the War of 1812. Together, Peabody and Riggs worked their way to the top of Baltimore’s merchant class.

In 1835, like most of the other former British colonies, Maryland was saddled with debt. They had taken out loans from London banks to finance railroads and canals, which they hoped would spur business and foster trade. When the new commerce failed to materialize, Maryland, like several other states, found herself in a financial pickle. Local hatred toward foreign bankers caused state legislatures to threaten to renege on the loans, and Peabody was selected to lead a commission to renegotiate the debt. Peabody successfully argued that only more loans would assure repayment of the old ones, and secured an additional $8 million for Maryland.

While in London, Peabody fell in love with the business and lifestyles of the city’s merchant bankers, and he decided to move there and form his own bank. In 1837, with a loan from Riggs, he did just that, setting up Peabody, Riggs and Co. at the prestigious address of 31 Moorgate in London. Now he was shoulder-to-shoulder with such banking luminaries as the Baring Brothers, who had financed the Louisiana Purchase, and the aforementioned Rothschilds.

But it was an uphill battle for Peabody in this new enterprise. State after state reneged on interest payments, and five American governors formed a debtor’s cartel leveraging for debt repudiations. Peabody’s partner, Riggs, wanted out of the arrangement, and Peabody was forced to go it alone. Moreover, entry into the celebrated society of British bankers – already difficult for an American – became impossible under the cloud of defaulted American loans.

But Peabody’s neighbor, the Barings Bank, was also stuck with defaulted bond issues, and together the two houses concocted a scheme to get the states back on good footing. The plot involved such shameless acts as paying newspapers to run editorials in favor of debt repayment, establishing a political slush fund to be used for electing (mostly Whig) pro-debt repayment legislators and even convincing clergymen to preach on the moral sanctity of contracts. They even bribed the orator and statesman Daniel Webster to make speeches on the topic.

The ploy worked. With a couple of exceptions, the depreciated state bonds that Peabody had bought up resumed interest payments, and Peabody reaped a fortune. Later, with revolution in Europe, a gold rush in California and a war with Mexico, American securities became the safe bet and the House of Peabody’s standing among the London merchant bankers was cemented.

Though known for his philanthropy later in his life, Peabody was friendless miser. “I have never forgotten and never can forget the great privations of my early years,” he once told an acquaintance. This scar upon his memory greatly affected his attitude toward money, and some have observed that the philanthropy for which he is remembered today was little more than an attempt to repair his reputation as a tightfisted loner.

Junius Morgan, who had become Peabody’s partner in 1854, later recounted an episode that perfectly illustrates Peabody’s stinginess. Upon arriving to work one morning, Morgan found Peabody at his desk looking pale and feverish. “Mr. Peabody, with that cold you ought not to stick here,” Morgan suggested. Peabody reluctantly agreed and proceeded home. Twenty minutes later, while on his way to the Royal Exchange, Morgan came upon Peabody standing in the driving rain. “I thought you were going home,” exclaimed Morgan. “Well I am, Morgan,” Peabody replied. “But there’s only been a two-penny bus come along as yet and I am waiting for a penny one.”

Peabody’s Parsimony extended to other matters, as well. In 1854, when Junius Spencer Morgan became Peabody’s only partner, part of the agreement was that in ten years’ time, Peabody would leave the reins – and the firm’s name – to Morgan. After nearly 30 years of work, the House of Peabody had become one of the pillars of international finance; continuing the name would help assure continued success. But in 1864, even as he was donating thousands to charities all over the world, he refused Morgan use of the Peabody name.

“It was, at that time, the bitterest disappointment of [his] life that Peabody refused to allow the old firm name to be continued,” Morgan’s grandson recalled. Morgan reluctantly changed the name to J.S. Morgan and Company.

Despite Peabody’s stinginess in personal matters, he was generous in his endowments to a wide variety of charities. He formed a trust fund to build housing for London’s poor. Called Peabody Estates, they had gas lamps and running water, unlike the fetid hovels that had hitherto served as the city’s poorhouses. The trust fund continues today, financing subsidized housing in London. He endowed a natural history museum at Yale, an archeology and ethnology museum at Harvard and an educational fund for emancipated southern blacks. Each of these gifts bore the Peabody name, which is why he is remembered even today for his philanthropy.

“Unlike later Morgan benefactions, often anonymous and discreet,” notes The House of Morgan author, Ron Chernow, “Peabody wanted his name plastered on every library, fund, or museum he endowed.” Unfortunately for Morgan, this did not extend to his banking house. “Perhaps in his new sanctity,” Chernow adds, “he wanted to erase his name from the financial map and enshrine it in the world of good works.”

When Peabody died in 1869, the British government prepared a grave for him at Westminster Abbey in an effort to recognize his generous endowment to London’s poor. But Peabody’s wish was to be buried in his birthplace, Danvers, Massachusetts. So, Queen Victoria arranged for his body to be transported stateside upon The Monarch, England’s newest and most formidable warship.

In 1946, Thomas Lamont, chairman of J.P. Morgan and Co., asked Lord Bicester, senior partner of Morgan Grenfell, the London branch of the bank, for a copy of Queen Victoria’s letter thanking Peabody for aiding London’s poor. Bicester replied in part:

“I have always understood that Mr. Peabody, though known as a great philanthropist, was one of the meanest men that ever walked…I believe he left several illegitimate children unprovided for.”

Check back later for more on J.P. Morgan and Co.

Posted by creation of the nation at 7:55 AM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory

Saturday, October 15, 2005

The Trickle-Up Theory (part 2)

- Butch Cassidy

Okay, so modern banking is a scam designed to fatten the rich at the expense of the poor. But how did it get that way?

Since its inception, banking has been crooked. The first banks appeared in ancient Egypt, Babylonia and Greece, where wealthy farmers and tradesmen deposited gold and silver in local temples for safekeeping. Pagan priests would loan the gold to needy families at rapacious interest rates and then split the proceeds with the depositors. Families that could not repay their loans were jailed, executed or sold into slavery. The church – which was also the government – grew exponentially rich, along with the depositors.

Banking grew in complexity during the Roman Empire, when the fortunes of war were deposited in private banking institutions, which were allowed to do what they pleased with the wealth as long as they helped finance further conquests. Private banks in Rome also helped finance the construction of roads, aqueducts, monuments and temples; laborers and soldiers were paid in salt, a valuable commodity at the time. (It is from this practice that we get the word “salary.”) If ever a private banker in ancient Rome got into hot water with his customers, all he had to do was finance a monument to the Caesar of the moment and the uprising would be quelled.

The middle ages saw the next great leap forward in banking with the advent monastic orders of knighted crusaders, most notably, the Knights Templar, who used stolen riches to expand their ranks and curry favor with the Papacy. Like the other monastic orders at the time of the crusades, the Knights Templar, or Knights of the Temple of Solomon, began in earnest, taking vows of celibacy and poverty. Their name was derived from the portion of Jerusalem they occupied after the Muslims had been driven out in the early 12th century. Legend had it that the mosque al-Aqsa in Jerusalem had been built on the site of the original Temple of Solomon. Since this was the quarter they inhabited during their occupation of Jerusalem, they began calling themselves the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon. Over the centuries, this name was shortened to the Knights of the Temple of Solomon, then later, Knights Templar.

The Knights Templar took their orders directly from the Pope and obeyed no other laws. This appealed to many noblemen despite the vows of celibacy and poverty, not to mention the harsh and dangerous existence led by the Knights Templar. Noblemen from all over Europe campaigned for admittance to the Knights Templar, offering their vast riches and land holdings as dowries. As a result, the Knights Templar grew in wealth and power, acquiring stately manors and immeasurable riches. They also gained a reputation as unparalleled stalwarts when it came to guarding their wealth.

At this point in history, wealthy noblemen had no method for protecting their riches from bandits and thieves other than to guard it themselves, which hindered other activities. Since the Knights Templar were already guarding their own vast riches, it would take no extra effort for them to guard other people’s riches, too. Before long, it became common practice for noblemen throughout Europe and the Middle East to give their riches to the Knights Templar for safekeeping. Soon, even governments adopted the practice: England even turned over a portion of the crown jewels to the Templars’ able watch.

The Templars quickly added other financial services to their repertoire, including debt and tax collection, loans and even cargo and passenger shipping. They issued notes to depositors who then traded the notes rather than transferring the actual gold and jewels. Thus was born the advent of paper money.

After nearly 200 years, the Knights Templar had grown richer and more powerful than most of the countries in Europe. More importantly, they had grown more powerful than the Vatican, a development that did not sit well with then Pope Clement V, who ordered the arrests of all the Knights Templar and the redistribution of their wealth, most of which went to Templar rivals, the Knights Hospitaller, who, rather than banking, had established what might be called the first hotel chain.

The early modern period saw the emergence of Jewish banking establishments. Since Christian doctrine forbade the collection of interest, and since most other professions were off limits to Jews, banking and money trading became primarily Jewish occupations.

In medieval times, just about every kingdom, duchy or realm had its own coinage, usually bearing a likeness of the duke or prince in power. A nobleman traveling from one kingdom to the next – often a distance of less than a hundred miles – would be compelled to have with him the coin of the realm. After all, the duke or prince in one province would be most offended indeed to see the face of his neighboring rival stamped on a coin. So, some method had to be devised that would ensure that travelers had the proper coinage in their purses. Local Jews, familiar with the various regional coins and their values, would often trade one coin for another for a small fee. Over the years, these small fees would add up, and the clever and thrifty moneychanger might, on occasion, find himself with a small fortune.

Oftentimes, these small fortunes were used to buy passage from Europe to Jerusalem, where the Arabs looked upon Jews with less disfavor than their European counterparts. Other times, however, moneychangers would stay put, using their wealth to curry favor with the local monarch. Frequently, this entailed financing a war or building an addition to the castle. The moneychanger would provide the necessary funds in exchange for later repayment plus interest, or, as in most cases, increased freedom. In the aptly named Dark Ages, the average Jew’s activities were severely restricted. A small loan to the local duke might earn letters of transit, which, despite the Jew’s low social standing, would be required to be honored by any local subject who wished to keep his head.

This is precisely the method Mayer Amschel Rothschild used to deliver his family from the Jewish slums of Frankfurt, Germany to the pinnacle of the now famous Rothschild banking house. In 1743, the year Rothschild was born, Jews were not even allowed surnames unless one was given to them by a local official. In the place of surnames, many Jews took the name of the house in which they were born. As this was before the advent of numbered address systems, most houses had a sign or plaque differentiating their house from the ones around it. Rothschild means Red Shield in German. Mayer Rothschild, therefore, means simply Mayer from the house with the Red Shield.

Mayer Rothschild was a trinket shop owner and moneychanger who collected rare and discontinued coins as a hobby. The local landgrave, Elector William I, shared Rothschild’s interest in rare coins and invited the young moneychanger to his castle to compare collections. Rothschild handled himself skillfully, offering several rare coins as a gift to the wealthy landgrave. Soon, Rothschild was named Elector’s financial agent.

Elector William I had made a fortune renting out his famed Hessian fighting men to kingdoms all over Europe. When his cousin, a Danish prince, requested a large loan for a war he was losing, Elector William I found himself in a quandary. He knew the loan would never be repaid in full, since the cousin would cite family ties as justification for reneging on the loan. He knew also that denying the request would do irreparable harm not only to familial relations, but also to the fragile political balance of the time. The clever Rothschild came to his rescue, devising a plan that would both preserve the delicate political situation and insure repayment of the loan. Rothschild concocted a scheme whereby the Danish prince would get the money without knowing who it came from. He would therefore be bound by honor to repay the loan.

This was Rothschild’s breakthrough. Not only did the stunt earn him permanent letters of transit for him and his family, it also laid the groundwork for a continent-wide messenger service that would surpass those of all the kingdoms of Europe. This service was used widely for many decades to come, since it was faster and more confidential than any other such service then in existence. What’s more, the confidentiality did not extend to the Rothschilds themselves; by reading the messages being sent via their service, the Rothschilds were finely attuned to the political and financial activities of all of Europe. This arrangement led eventually to the Rothschilds’ virtual takeover of the British stock market and, therefore, their ascension to European aristocracy.

Mayer Rothschild’s five sons went on to form the largest banking conglomerate in the world, with branches in London, Paris, Vienna, Naples and Frankfurt. Their immense wealth and influence deeply affected the political landscape for many decades. The Rothschild’s achievements include the building of the Suez Canal, the Cape Town to Cairo railway, the formations of Rhodesia and Israel, and the rise of the De Beers diamond concern, to name just a few. The Rothschild’s influence had diminished significantly by the 20th century. The rise of Hitler forced them out of Germany and Austria; the annexation of Naples by Italy brought a halt to the Naples branch of the bank; and the emergence of national banks in England and France greatly reduced their influence in those countries. But the Rothschilds’ effect on the contemporary political topography can still be deeply felt. The current Rothschild generation is active in philanthropy, the arts and politics. Their impact cannot be overstated.

Posted by creation of the nation at 8:44 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory

Tuesday, October 11, 2005

The Trickle-Up Theory (part 1)

How Banks Prey on the Poor

When I was about eight years old, I opened my first bank account. It was a passbook savings account, and I’ll never forget the smiles on the bank managers’ faces as they patiently helped me fill in all the necessary paperwork. At the time, I assumed the smiles were inspired by the cute novelty of a little boy opening his first account, but upon reflection, I realize they were smiling at me the way Dracula smiles at his next victim.

“Come hither,” they beckoned helpfully. “I think you’ve got something on your neck.”

That experience 30 years ago was my last pleasant banking transaction. Since then, my banking career has been a nightmare of hidden fees, overdraft charges, denied loan applications and collection agents. Banks refer to their victims as customers, but a customer is someone whose repeat business one is trying to earn. Banks act as if they are doing you a favor by allowing you to open an account.

I have a friend who refuses to open a bank account. He keeps his money in a cookie jar on the top shelf of his cupboard. When he gets the desire to buy something like a new computer or a stereo, he simply saves his cash in the cookie jar until there’s enough to make the purchase in question. He pays his rent in cash; he buys money orders for his utility bills and all other expenses for which cash is inappropriate.

I used to make fun of him for his lowbrow approach to finance. Many times I derisively told him of the old Lithuanians I saw while waiting in line at my bank in Chicago who would come in every Saturday to count their money. The bank tellers wore expressions of frustrated resignation as the distrustful oldsters would demand to see their money and count it. I laughed cruelly at the way the old guys never realized that it was the same $5 thousand being counted over and over.

But who’s laughing now? As I write this, my checking account is overdrawn by $149.00. Every day it’s in the red, they add another $5.00. Are they doing this to earn my repeat business?

Those old Lithuanians are right to distrust banks. And so is my friend. Here’s why:

There are several methods banks use to extract as much money from their customers as possible. I should say from their poor customers, because the true purpose of almost every bank is to serve the rich at the expense of the poor. According to the New York Times, banks received over $30 billion in overdraft fees in 2001. Rather than offering overdraft protection to the working poor at a reasonable interest rate of, say, 10 to 20 percent, depending on the customer’s credit worthiness and length of employment, banks instead agree to cover bounced checks and debit card transactions and charge a fee of $20.00 to $35.00 for each overdraft. That means the $2.00 cup of coffee you purchase using your debit card two days before payday could end up costing you $37.00 or more. In effect, the bank is offering you a loan at an interest rate of around 190 percent. If you tack on the $5.00 or more per day many banks charge overdrawn accounts, the percentage rate climbs to over one thousand percent. That had better be one damn good cup of coffee.

But that’s not all. Most banks use many shady tricks to maximize the possibility of your being overdrawn. Here’s one little trick banks use to exploit their working class clientele:

Let’s say you have written several checks this week. The first check was for $650 for your rent or mortgage payment. The second check was for $45 for your phone bill. The next two checks were for around $20 apiece for gas and electric service. Then another one for around $40 or $50 for groceries. Then, throughout the week, you wrote three or four more checks for between $5 and $10 apiece for lunch. On top of that, you stopped for coffee a couple times on your way to work and wrote checks for around $2 each time. Throw in a pack of smokes or a six-pack of beer here and there and by payday, you’ve overdrawn your account by $15 or $20. Well, rather than debiting all the small checks first and then charging the $35 overdraft fee for the $650 rent payment, they debit the largest checks first so that they can charge the $35 overdraft fee several times over on all the little checks. Don’t believe me? Check your bank statement at the end of the month.

What’s more, most banks increase the overdraft charge if you’ve had more than a certain number of overdrafts in a given period of time. If you’re like me, the first pay period of the month can be difficult because rent and most utility bills are due by the 5th of the month. The obvious solution is to apply for overdraft protection. Overdraft protection provides the customer with a line of credit that kicks in automatically when expenditures exceed the amount of money in the customer’s account. The loan is paid back usually at an interest rate similar to that of most credit cards.

Unfortunately, the bank customers who need this service the worst – ones who find themselves in the red about once per month – are the ones least likely to be approved for such protection because they are considered bad credit risks. Paradoxically, one of the things the bank looks at in considering customers for overdraft protection is how many overdrafts the customer has had within the last 18 months or so. When my application for overdraft protection was denied for this very reason, I decided to create my own overdraft protection. My current financial tormenter, U.S. Bank, offers a service called a “goal savings account.” This service automatically transfers a certain amount of money – in my case, $25 – from my checking account into my savings account once per month. Since they would not approve me for overdraft protection, I asked them if they would set up my accounts such that if I overdrew my checking account, the needed sum would be transferred automatically from my “goal savings account.” They gladly agreed. What they failed to mention, however, is that each time such a transfer occurs, my account is charged $5. So, if I have $2 in my checking account and I write a check for $5, it will cost me $5 to transfer $3 from my “goal savings account” to my checking account. Their failure to notify me of the $5 charge resulted in both my accounts being overdrawn.

In effect, U.S. Bank – like all banks I’ve encountered – is like a shark, no wait, a vulture, pouncing on the animal in distress and regurgitating the digested flesh into the waiting mouths of the rich who sit uselessly squawking in the nest. Or something like that.

When you take all this into consideration, the word “customer” takes on tragicomic dimensions. What if a tailor treated his customers the way banks treat theirs? If he knew you were poor, he would sew the buttons onto your shirts in a way that guaranteed they would pop off the second or third washing and then charge you to replace them and increase the replacement charge by 10 percent every fifth button. He would simultaneously do exquisite work for his rich customers while giving them deep discounts and free alterations and repairs. Plus, he would be rude and dismissive every time you entered his shop. Come to think of it, this is precisely what tailors do, only they’re not tailors any more, they’re The Gap.

To add insult to injury, the advertising campaigns for most banks are patently dishonest. TCF Bank in Minnesota claims in their ads to offer “totally free checking,” while First Bank in Kansas tells its customers to “relax…you deserve consideration.” This advertising approach gives prospective customers the false impression that if, like roughly 3 million Americans, they are living paycheck to paycheck and find themselves in financial difficulty from time to time, they can count on the bank to help them out. This is a reasonable assumption. Why else, after all, would someone choose to keep his or her money in a bank?

There are three reasons that I can think of. First, banks are insured. If the bank is robbed or destroyed in a fire or tornado or some such calamity, the customers’ money remains safe and sound, whereas if my friend’s cookie jar is stolen or destroyed, he’s shit outta luck. Second, customers can earn interest on their deposit, albeit a tiny percentage. The third and most compelling reason someone might want to keep his or her money in a bank is Purchasing Power. If, like many Americans, you find yourself a little light towards the end of the pay period, you can simply “relax” because “you deserve consideration.” This relaxation, though, comes at a very high price. And the poorer you are, the higher the price.

Another scheme employed by many banks is a system of bizarre and constantly changing rules regarding when deposits and account transfers are posted. If, for instance, you make the deposit in person at a teller, it posts at one time, but if you make the deposit at an ATM, it posts at a different time. Many banks offer a 24-hour telephone line that customers can call to check their account balance, but this, too, is a ruse. On more than one occasion, I have called the number and made a purchase based on the balance information provided only to incur an overdraft charge because some previous purchase or debit was not yet reflected in the amount stated.

The American Heritage Dictionary defines customer simply as “one who buys goods or services,” but the American banking system has its own definition: “One who pays a lot for services, but receives only punishment.”

There is a tiny ray of hope, however, for the working poor who prefer not to keep their money in a cookie jar. It’s called the Credit Union.

Credit Unions are non-profit (if there is such a thing) banking institutions that, for the most part, act in the best interests of their customers. The idea behind credit unions is that, as with all unions, individuals obtain more power and autonomy when they work together.

The first credit unions were closely associated with labor unions. Teachers or plumbers or carpenters or journalists would pool their financial resources to provide low interest loans to the union’s neediest members, thereby providing assistance to working families who had been forsaken by traditional banks. The problem was that in order for credit unions to retain their non-profit, tax-exempt status, membership was required to be restricted to particular groups, such as trade unions or farmers or very small geographical areas such as townships or counties.

The Credit Union Membership Act of 1998 changed all that. This act allowed credit unions to significantly expand their eligibility without endangering their non-profit, tax exempt status. As a result, credit union membership has grown from about 64 million members in 1992 to almost 83 million members in 2002. And according to the Christian Science Monitor, Credit union-issued loans increased from a 16.1 percent share of the national market in 1992 to 17.1 percent in 2002.

Of course, traditional banks are pissed off about this development. And why shouldn’t they be? The $30 billion-per-year overdraft cash cow upon which they’ve been feeding is walking out the door.

“Once, members of a credit union knew each other and pooled their resources to provide credit for their co-workers and neighbors,” laments the American Banking Association web site. Today, the diatribe continues, credit unions can serve entire states. “Despite this departure from their original mission, these credit unions continue to be afforded special treatment, including exemption from federal taxation and from the regulatory responsibilities that apply to commercial banks.”

Well, boo hoo. Congress has acted on behalf of its constituents, for a change. Whatever will those poor, mistreated banks do now? I guess they’ll just have to take their $30 billion bat and ball and go home. When will these insouciant greed heads ever learn? Had they treated their working class customers with respect when they had the chance, they wouldn’t be witnessing this exodus into credit unions today.

But this doesn’t mean things are all peaches and cream for working class Americans. Credit unions still require a credit application to qualify for loans and overdraft protection, and with many such customers emerging bruised and battered from commercial banking’s rapaciousness, credit histories unfairly reflect poor ratings.

to be coninued

Posted by creation of the nation at 8:21 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory