Friday, December 31, 2010

Kevin Spacey Channels Al Pacino

Posted by creation of the nation at 10:02 AM 0 comments

Labels: bureaucrats, conspiracies, Trickle Up Theory

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

IMF'd

Well, the worldwide socialist takeover the Birchers have been warning us about is coming to fruition, but it's a little different than what they had in mind. It's socialism for the bank$ters, but feudalism for everyone else, and unlike the with Thatcher/Reagan '80s, there doesn't seem to be a dot-com escape hatch this time.

Devo was right. Freedom from choice is what we want, but the illusion of choice is what we've got, and now the Corporate Feudal State is upon us. But, hey, if you're not doing anything wrong, you've got nothing to worry about. Shut up. Be happy. The number one enemy of progress is questions.

Posted by creation of the nation at 9:55 PM 0 comments

Labels: irrational murderous rage, social justice, Trickle Up Theory

Sunday, May 18, 2008

The Kinks -- Low Budget

"Americans, like human beings everywhere, believe many things that are obviously untrue. Their most destructive untruth is that it is very easy for any American to make money. They will not acknowledge how in fact hard money is to come by, and, therefore, those who have no money blame and blame and blame themselves. This inward blame has been a treasure for the rich and powerful, who have had to do less for their poor, publicly and privately, than any other ruling class since, say, Napoleonic times."

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five

Posted by creation of the nation at 10:30 PM 0 comments

Labels: Music Video, Trickle Up Theory

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

The Shock Doctrine

Posted by creation of the nation at 6:53 AM 0 comments

Labels: conspiracies, paranoia, psychotic leaders, social justice, Trickle Up Theory

Monday, September 3, 2007

The American Dream is a Lie

In 1998, I had a temp job at a local Ameriquest Mortgage affiliate. The assignment lasted from right before Thanksgiving to right before Christmas.

God, that job sucked.

Mainly, my job was to enter mortgage information into a database, but they would occasionally ask me to perform other tasks, such as driving to the Government Center to hunt down information on recently filed foreclosure notices. That was the modus operandi at this office – locate desperate families who were about to lose their homes and offer them a refinancing deal. It didn’t hurt that it was Christmastime.

When I asked my supervisor, a wiry bleach blond mother of three from a far away suburb, why the database included race information, she said it was just a legal technicality. “Don’t worry,” she reassured me, “there’s no racism anymore.” After that, I started marking every entry as “Caucasian, non-Hispanic.” I don’t know if that helped or hurt, but I had to do something subversive. In the anteroom where the coffeemaker and fax machine were, the walls were decorated with news clippings. Every one of them was about ACORN, the non-profit group that helps working class families buy homes. Names of ACORN representatives were highlighted in yellow with nasty remarks written in the margins.

Since it was autumn, hunting and football were the main topics of conversation. And of course children. “Blah blah blah hunting,” they would say. And “blah blah blah football.” And of course, “blah blah blah family.” Since I didn’t hunt, watch football or have children, I was like half a fag in their eyes. Politics were carefully avoided, probably on orders from the Main Office or something, but it didn’t take a rocket surgeon to figger out who these dolts voted for in the last election. (HINT: Bob Dole)

Anyway, flash forward nine years. Now I’m working for the second largest settlement administrator in the country (yes, I’m temping again) handling the class action settlement against – you guessed it – Ameriquest. According to the badly spelled script we are supposed to be reading to the class members, all 50 states except Virginia (supposedly because Ameriquest never did business in Virginia) have found Ameriquest guilty of violating just about every law governing home loans. They provided deceptive information on interest rates and discount points, convinced homeowners to refinance when doing so provided no benefit to the borrower, and they falsified borrowers’ financial information in order to maximize the loan amounts.

Here’s how a class action settlement works, for those of you who, like me, were never very clear on the concept: What happens is, somebody sues someone. Then another person sues that same entity for more or less the same reasons. Then another person does it. Then another. After awhile, it becomes apparent that the entity being sued perpetrated the alleged crime on numerous individuals. Said individuals are then identified as a ‘class.’ Efforts are made to locate all of the class members – in this case, anyone who had a loan with Ameriquest between 1999 and 2005. (I’m not sure how those dates were arrived at, since the bad behavior extends beyond them.) If the defendant is found guilty (or about to be found guilty), they offer a settlement to be divided among the class members. If the majority of the class members accepts the settlement, then the whole thing is settled. If the majority of the class members fails to accept the settlement, then it’s back to the drawing board. In the case of Ameriquest, the average settlement amount is around $600. Naturally, Ameriquest wants everyone to accept the settlement, since it means the company will pay out a mere fraction of what they stole. Class members are faced with the choice of accepting the settlement and at least getting something, or refusing the settlement, hiring an attorney and going it alone in the hopes of getting the tens of thousands they are really owed. Since most of the class members were poor to begin with, or at least not rich, this latter option is usually beyond their reach, unless they know a lawyer willing to help them out pro bono. One fly in Ameriquest’s ointment is the fact that many of the class members have lost their homes and are now unreachable using the information in Ameriquest’s databases. If less than a certain percentage of the class members accept the settlement, either intentionally or because they couldn’t be reached in time, then new settlement arrangements must be arrived at.

For some strange reason, there is very little mention of the class action lawsuit against Ameriquest in the supposedly liberal media.

As I mentioned above, Rust Consulting is the second largest settlement administrator in the country, a fact they are eager to repeat at every opportunity. I probably shouldn’t be linking to them, since they are kinky for confidentiality and this will probably come back to haunt me somehow. One observation I have made on this assignment, or I should say, one suspicion I have long had which has been emphatically confirmed on this assignment, is that the American educational system is woefully inadequate. Both my fellow temps, and the class members I am calling at a rate of 30 per hour, display a shocking incapacity for basic communication and reasoning skills. For example, whatever happened to the tradition of keeping a pen and paper near the telephone in case you need to write something down? Time and again, I am forced to wait while someone laboriously searches for a pen, and even then I must spell nearly every word of the two-sentence message while they scratch it out Ali G style. “…Set-tle-ment,” I repeat patiently. “S-E-T-T-L-E-M-E-N-T. Ad-min-ist-rat-or. A-D-M-I…” I hang up knowing that not one word of the message will reach its intended recipient in any meaningful form.

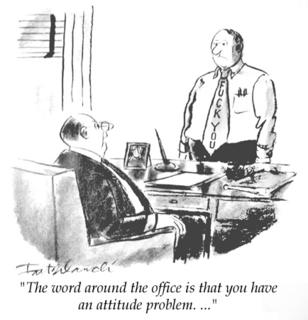

I can tell by the uneasy expressions I receive from my supervisors whenever we talk that I am an anomaly among the temp crowd in that I catch on quickly and use relatively good grammar in my daily speech. There must be something wrong with me, they suspect, since I am not borderline retarded. What I mean is, there must be something wrong with me that isn’t readily apparent; there is something wrong with nearly all of my coworkers, but you can tell what it is at first glance. With me, the problem is lurking below the surface somewhere, and that fills my supervisors with unease. I think some of them suspect me as some sort of corporate spy – perhaps from Ameriquest or one of the law firms – sent here to make sure they are handling things professionally. But maybe I’m just being paranoid. In any case, they are right that something is lurking beneath the surface; it’s an irrepressible urge to speak truth to power, which is precisely why I keep landing in these crappy temp jobs in the first place. The American workplace, from the White House on down, craves obedience. Independent thinking, even if it is used to accomplish the tasks at hand, is a Major Threat that needs to be extinguished quickly before it spreads. Likes golf? Check. NASCAR? Check. Hooters? Check. Sinclair Lewis? WARNING WARNING WARNING…

On Friday, August 17th, 40 or 50 of us temps crowded into a hotel conference room to receive our “orientation,” which consisted mainly of reiterating Rust Consulting’s extremely high level of ethics, and repeating the importance of being at our workstations on time each morning and after every break. And speaking of breaks, these are rigidly enforced. Unfortunately, the process for punching in and out for breaks consumes nearly a third of the break time.

On Monday, August 20th, we arrived for our first shift. We were forced to wait in the lobby for nearly 40 minutes before we were allowed through the front doors. The delay was never explained. We didn’t get to punch in until after 9 am, over an hour after our agreed upon start time. What I deduce from this, naturally, is that our time is worthless to Rust Consulting, but that Rust’s time must be regarded as precious to the temps. Bryan, one of my many supervisors, spent most of the morning filling out MAF forms for each of us to sign. MAF stands for Manual Adjustment Form, and one must be filled out anytime there is an error in the electronic timekeeping system; for example, if you forget to punch out for break, you need to fill out a MAF, and it needs to be signed by you, your supervisor and the HR director.

The scripts we were expected to read to the class members over the telephone went through many rewrites, exacerbating the already awkward task of calling strangers and reading to them. We were instructed to read the scripts “conversationally,” which is impossible since they are laden with legalese. Well, not legalese so much as excruciating ass-covering detail. For instance, you can’t say “the tenth,” or “Monday the tenth;” you have to say, "Monday, September 10th, 2007." Every. Fucking. Time. How do you do that “conversationally?” Not even Spock speaks that formally. There is always somebody listening to your phone calls, and from time to time one of the many supervisors appears with a checklist that you must sign grading your performance. The most common criticism is that you didn’t adhere to the script. The script is so poorly written though, that you cannot adhere to it without splitting infinitives and dangling participles.

The class members we are calling – that is, the ones who haven’t yet lost their homes – already stinging from the flogging they have received at the hands of Ameriquest, become belligerent the moment the word “Ameriquest” is uttered. That’s the only word from the whole script that they seem to hear. If they don’t just hang up, which is understandably common, they blurt out some variation of “the check’s in the mail.” About half the time, it takes a solid 30 seconds of arguing just to get them to understand that they are eligible to receive money this time, and of course you can’t do so at all without deviating from the script. We are expected to make a minimum of 25 calls per hour. Since either Ameriquest or Rust has screwed the pooch on this deal, we are having a hard time reaching all 200,000 or so of the class members before the September 5th deadline. As a result, overtime is available for the temps who aren’t ready to pull their hair out at the end of their regular shift. But in order to be considered for overtime, you must make at least 30 calls per hour. As a result, most of my coworkers read the script in an unintelligible monotone that results inevitably in even more hang-ups. Hang-ups are good, since they only take a few seconds. I suspect that the whole thing is designed to minimize the possibility of actually making contact with all the class members. But maybe that’s just me being paranoid again.

I wish I could've been there at the Ameriquest branch when the chickens started coming home to roost and people were getting laid off and the phones weren't ringing except when the lawyers called and it became painfully obvious that, yes, you self-absorbed suburban white trash twat, racism is still alive and well in the Land of the Free. It's about the only time I've wished to be at a temp job.

As is so often the case, corporate America has pitted two groups of poor people against one another in their interminable effort to evade justice. One group, so desperate for meaningful employment that they will immerse themselves in an absurd tragicomedy just to make ends meet, is forced to attempt contact with the other group of poor people who foolishly believed in something that vanished around 1950, if it ever even existed at all – the American Dream.

Posted by creation of the nation at 9:39 PM 0 comments

Labels: Trickle Up Theory, work

Tuesday, February 27, 2007

Trickle Up Economics

Frequent readers of BDM (all six of you), have probably encountered a term I think I coined: the Trickle Up Theory.

As you have probably guessed, "Trickle Up Theory" is my somewhat snotty response to the Trickle Down Theory of economics, which seems to rear its ugly head at least once per decade. The Reaganites called it Reganomics, natch; the Clintonites called it “supply-side” economics. Not sure what Bush Inc. is calling it, “nukuler smok-em-out” economics, probably.

Of course, supply-side economics doesn’t work. Cutting taxes for these guys doesn’t spur economic growth. Nor does it create jobs, increase wages or generate income, as its proponents would have you believe. All it does is make these guys richer. And their mistresses too.

And where does all that money come from? From us. That’s why I call it the Trickle Up Theory. Money trickles up from us po’ folk to the rich. Get it? There are lots of mechanisms in place to facilitate this poor-to-rich trickle—insurance companies, temp agencies, banks, governments, debt collectors—so much so that it’s actually a stream. Perhaps even a torrent.

Here’s a good example of locally grown (groan) Trickle Up Economics. Here’s the global variety.

Anyhoo.

Another thing I’ve noticed about Trickle Up Economics is that as money trickles up to the rich, accounting prowess trickles down to the poor. That is, the most fastidiously accurate accountants seem to be hanging around us lowly wage earners, while the really incompetent accountants seem to be working for huge government agencies and global investment firms and multi-billion-dollar military contractors and stuff. Life is full of ironies, I guess.

Take the Pentagon, for example. According to some estimates, the Pentagon has lost $2.3 trillion. That’s right—trillion.

Dollars.

Lost.

That’s roughly $8,000 per American. Meanwhile, the U.S. Dept. of Education is after me for the $800 I still owe on my student loans. I’ll tell you what, Dept. of Education, as soon as the Pentagon finds the $2.3 trillion, I’ll cough up the $800 out of my share. How’ll that be? Super.

I have a letter from Xcel Energy magneted to my fridge. Xcel Energy is the multi-state energy company once headed by former Energy Secretary Hazel O’Leary back when it was known as Northern States Power. After O’Leary’s four scandal-plagued years with the Clinton regime, NSP wisely changed its name.

But back to the letter. The letter from Xcel Energy was sent to inform me that there was one cent left over from the account at my previous apartment, and that they are transferring said amount to the account at my new address. Once cent. Now that’s efficiency!

Hey! I’ve got an idea! Let’s take all the Xcel Energy accountants and trade them to the Pentagon. The Pentagon accountants can then work for Xcel. I mean, a penny here or there doesn’t really matter that much. I’m confident that Xcel can make up the difference from the occasional missing penny. But the Pentagon clearly needs help.

Well, that was easy. (yawn) Maybe tomorrow I’ll tackle NASA.

Posted by creation of the nation at 9:50 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory

Tuesday, November 8, 2005

The Trickle-Up Theory (part 3)

The other monolithic figure of early modern banking was the House of Morgan. Led by the notorious J.P. Morgan (junior and senior), the Morgan bank stood atop the international financial world for over a century, controlling railroads, telegraph networks, mining concerns, shipping lines, lumber, oil and steel conglomerates and greatly influencing the politics of four continents. At its height, the House of Morgan simultaneously symbolized all that is good and bad about American capitalism. J.P. Morgan was an original patron of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gave generously to the American Museum of Natural History and St. Luke’s Hospital, kept a seldom-occupied box at the Metropolitan Opera and helped launch the legendary Groton prep school. At the same time, his bank loaned money to fascist Italy, bankrolled Mussolini’s American P.R. campaign and financed wars on at least three continents.

Morgan, along with the other influential banks of the day, National City Bank, Kuhn Loeb and Co., and Brown Bros. Harriman, ushered in the era of globalism that now dominates international trade; and their “gentleman Banker’s Code” would be considered insider trading by today’s standards. Nevertheless, for good or ill, the House of Morgan was instrumental in America’s rise to its present position as the world’s lone superpower.

Like the Rothschilds before it, the House of Morgan has humble beginnings. Originally called the House of Peabody, the bank was founded by a rags-to-riches Baltimore dry-goods merchant named George Peabody. Peabody dropped out of school when his father died and went to work in his brother’s shop to support his widowed mother and six siblings. His flair for business gained him the capital to move to Baltimore and buy into a partnership with successful merchant Elisha Riggs, whom he met while fighting in the War of 1812. Together, Peabody and Riggs worked their way to the top of Baltimore’s merchant class.

In 1835, like most of the other former British colonies, Maryland was saddled with debt. They had taken out loans from London banks to finance railroads and canals, which they hoped would spur business and foster trade. When the new commerce failed to materialize, Maryland, like several other states, found herself in a financial pickle. Local hatred toward foreign bankers caused state legislatures to threaten to renege on the loans, and Peabody was selected to lead a commission to renegotiate the debt. Peabody successfully argued that only more loans would assure repayment of the old ones, and secured an additional $8 million for Maryland.

While in London, Peabody fell in love with the business and lifestyles of the city’s merchant bankers, and he decided to move there and form his own bank. In 1837, with a loan from Riggs, he did just that, setting up Peabody, Riggs and Co. at the prestigious address of 31 Moorgate in London. Now he was shoulder-to-shoulder with such banking luminaries as the Baring Brothers, who had financed the Louisiana Purchase, and the aforementioned Rothschilds.

But it was an uphill battle for Peabody in this new enterprise. State after state reneged on interest payments, and five American governors formed a debtor’s cartel leveraging for debt repudiations. Peabody’s partner, Riggs, wanted out of the arrangement, and Peabody was forced to go it alone. Moreover, entry into the celebrated society of British bankers – already difficult for an American – became impossible under the cloud of defaulted American loans.

But Peabody’s neighbor, the Barings Bank, was also stuck with defaulted bond issues, and together the two houses concocted a scheme to get the states back on good footing. The plot involved such shameless acts as paying newspapers to run editorials in favor of debt repayment, establishing a political slush fund to be used for electing (mostly Whig) pro-debt repayment legislators and even convincing clergymen to preach on the moral sanctity of contracts. They even bribed the orator and statesman Daniel Webster to make speeches on the topic.

The ploy worked. With a couple of exceptions, the depreciated state bonds that Peabody had bought up resumed interest payments, and Peabody reaped a fortune. Later, with revolution in Europe, a gold rush in California and a war with Mexico, American securities became the safe bet and the House of Peabody’s standing among the London merchant bankers was cemented.

Though known for his philanthropy later in his life, Peabody was friendless miser. “I have never forgotten and never can forget the great privations of my early years,” he once told an acquaintance. This scar upon his memory greatly affected his attitude toward money, and some have observed that the philanthropy for which he is remembered today was little more than an attempt to repair his reputation as a tightfisted loner.

Junius Morgan, who had become Peabody’s partner in 1854, later recounted an episode that perfectly illustrates Peabody’s stinginess. Upon arriving to work one morning, Morgan found Peabody at his desk looking pale and feverish. “Mr. Peabody, with that cold you ought not to stick here,” Morgan suggested. Peabody reluctantly agreed and proceeded home. Twenty minutes later, while on his way to the Royal Exchange, Morgan came upon Peabody standing in the driving rain. “I thought you were going home,” exclaimed Morgan. “Well I am, Morgan,” Peabody replied. “But there’s only been a two-penny bus come along as yet and I am waiting for a penny one.”

Peabody’s Parsimony extended to other matters, as well. In 1854, when Junius Spencer Morgan became Peabody’s only partner, part of the agreement was that in ten years’ time, Peabody would leave the reins – and the firm’s name – to Morgan. After nearly 30 years of work, the House of Peabody had become one of the pillars of international finance; continuing the name would help assure continued success. But in 1864, even as he was donating thousands to charities all over the world, he refused Morgan use of the Peabody name.

“It was, at that time, the bitterest disappointment of [his] life that Peabody refused to allow the old firm name to be continued,” Morgan’s grandson recalled. Morgan reluctantly changed the name to J.S. Morgan and Company.

Despite Peabody’s stinginess in personal matters, he was generous in his endowments to a wide variety of charities. He formed a trust fund to build housing for London’s poor. Called Peabody Estates, they had gas lamps and running water, unlike the fetid hovels that had hitherto served as the city’s poorhouses. The trust fund continues today, financing subsidized housing in London. He endowed a natural history museum at Yale, an archeology and ethnology museum at Harvard and an educational fund for emancipated southern blacks. Each of these gifts bore the Peabody name, which is why he is remembered even today for his philanthropy.

“Unlike later Morgan benefactions, often anonymous and discreet,” notes The House of Morgan author, Ron Chernow, “Peabody wanted his name plastered on every library, fund, or museum he endowed.” Unfortunately for Morgan, this did not extend to his banking house. “Perhaps in his new sanctity,” Chernow adds, “he wanted to erase his name from the financial map and enshrine it in the world of good works.”

When Peabody died in 1869, the British government prepared a grave for him at Westminster Abbey in an effort to recognize his generous endowment to London’s poor. But Peabody’s wish was to be buried in his birthplace, Danvers, Massachusetts. So, Queen Victoria arranged for his body to be transported stateside upon The Monarch, England’s newest and most formidable warship.

In 1946, Thomas Lamont, chairman of J.P. Morgan and Co., asked Lord Bicester, senior partner of Morgan Grenfell, the London branch of the bank, for a copy of Queen Victoria’s letter thanking Peabody for aiding London’s poor. Bicester replied in part:

“I have always understood that Mr. Peabody, though known as a great philanthropist, was one of the meanest men that ever walked…I believe he left several illegitimate children unprovided for.”

Check back later for more on J.P. Morgan and Co.

Posted by creation of the nation at 7:55 AM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory

Saturday, October 15, 2005

The Trickle-Up Theory (part 2)

- Butch Cassidy

Okay, so modern banking is a scam designed to fatten the rich at the expense of the poor. But how did it get that way?

Since its inception, banking has been crooked. The first banks appeared in ancient Egypt, Babylonia and Greece, where wealthy farmers and tradesmen deposited gold and silver in local temples for safekeeping. Pagan priests would loan the gold to needy families at rapacious interest rates and then split the proceeds with the depositors. Families that could not repay their loans were jailed, executed or sold into slavery. The church – which was also the government – grew exponentially rich, along with the depositors.

Banking grew in complexity during the Roman Empire, when the fortunes of war were deposited in private banking institutions, which were allowed to do what they pleased with the wealth as long as they helped finance further conquests. Private banks in Rome also helped finance the construction of roads, aqueducts, monuments and temples; laborers and soldiers were paid in salt, a valuable commodity at the time. (It is from this practice that we get the word “salary.”) If ever a private banker in ancient Rome got into hot water with his customers, all he had to do was finance a monument to the Caesar of the moment and the uprising would be quelled.

The middle ages saw the next great leap forward in banking with the advent monastic orders of knighted crusaders, most notably, the Knights Templar, who used stolen riches to expand their ranks and curry favor with the Papacy. Like the other monastic orders at the time of the crusades, the Knights Templar, or Knights of the Temple of Solomon, began in earnest, taking vows of celibacy and poverty. Their name was derived from the portion of Jerusalem they occupied after the Muslims had been driven out in the early 12th century. Legend had it that the mosque al-Aqsa in Jerusalem had been built on the site of the original Temple of Solomon. Since this was the quarter they inhabited during their occupation of Jerusalem, they began calling themselves the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon. Over the centuries, this name was shortened to the Knights of the Temple of Solomon, then later, Knights Templar.

The Knights Templar took their orders directly from the Pope and obeyed no other laws. This appealed to many noblemen despite the vows of celibacy and poverty, not to mention the harsh and dangerous existence led by the Knights Templar. Noblemen from all over Europe campaigned for admittance to the Knights Templar, offering their vast riches and land holdings as dowries. As a result, the Knights Templar grew in wealth and power, acquiring stately manors and immeasurable riches. They also gained a reputation as unparalleled stalwarts when it came to guarding their wealth.

At this point in history, wealthy noblemen had no method for protecting their riches from bandits and thieves other than to guard it themselves, which hindered other activities. Since the Knights Templar were already guarding their own vast riches, it would take no extra effort for them to guard other people’s riches, too. Before long, it became common practice for noblemen throughout Europe and the Middle East to give their riches to the Knights Templar for safekeeping. Soon, even governments adopted the practice: England even turned over a portion of the crown jewels to the Templars’ able watch.

The Templars quickly added other financial services to their repertoire, including debt and tax collection, loans and even cargo and passenger shipping. They issued notes to depositors who then traded the notes rather than transferring the actual gold and jewels. Thus was born the advent of paper money.

After nearly 200 years, the Knights Templar had grown richer and more powerful than most of the countries in Europe. More importantly, they had grown more powerful than the Vatican, a development that did not sit well with then Pope Clement V, who ordered the arrests of all the Knights Templar and the redistribution of their wealth, most of which went to Templar rivals, the Knights Hospitaller, who, rather than banking, had established what might be called the first hotel chain.

The early modern period saw the emergence of Jewish banking establishments. Since Christian doctrine forbade the collection of interest, and since most other professions were off limits to Jews, banking and money trading became primarily Jewish occupations.

In medieval times, just about every kingdom, duchy or realm had its own coinage, usually bearing a likeness of the duke or prince in power. A nobleman traveling from one kingdom to the next – often a distance of less than a hundred miles – would be compelled to have with him the coin of the realm. After all, the duke or prince in one province would be most offended indeed to see the face of his neighboring rival stamped on a coin. So, some method had to be devised that would ensure that travelers had the proper coinage in their purses. Local Jews, familiar with the various regional coins and their values, would often trade one coin for another for a small fee. Over the years, these small fees would add up, and the clever and thrifty moneychanger might, on occasion, find himself with a small fortune.

Oftentimes, these small fortunes were used to buy passage from Europe to Jerusalem, where the Arabs looked upon Jews with less disfavor than their European counterparts. Other times, however, moneychangers would stay put, using their wealth to curry favor with the local monarch. Frequently, this entailed financing a war or building an addition to the castle. The moneychanger would provide the necessary funds in exchange for later repayment plus interest, or, as in most cases, increased freedom. In the aptly named Dark Ages, the average Jew’s activities were severely restricted. A small loan to the local duke might earn letters of transit, which, despite the Jew’s low social standing, would be required to be honored by any local subject who wished to keep his head.

This is precisely the method Mayer Amschel Rothschild used to deliver his family from the Jewish slums of Frankfurt, Germany to the pinnacle of the now famous Rothschild banking house. In 1743, the year Rothschild was born, Jews were not even allowed surnames unless one was given to them by a local official. In the place of surnames, many Jews took the name of the house in which they were born. As this was before the advent of numbered address systems, most houses had a sign or plaque differentiating their house from the ones around it. Rothschild means Red Shield in German. Mayer Rothschild, therefore, means simply Mayer from the house with the Red Shield.

Mayer Rothschild was a trinket shop owner and moneychanger who collected rare and discontinued coins as a hobby. The local landgrave, Elector William I, shared Rothschild’s interest in rare coins and invited the young moneychanger to his castle to compare collections. Rothschild handled himself skillfully, offering several rare coins as a gift to the wealthy landgrave. Soon, Rothschild was named Elector’s financial agent.

Elector William I had made a fortune renting out his famed Hessian fighting men to kingdoms all over Europe. When his cousin, a Danish prince, requested a large loan for a war he was losing, Elector William I found himself in a quandary. He knew the loan would never be repaid in full, since the cousin would cite family ties as justification for reneging on the loan. He knew also that denying the request would do irreparable harm not only to familial relations, but also to the fragile political balance of the time. The clever Rothschild came to his rescue, devising a plan that would both preserve the delicate political situation and insure repayment of the loan. Rothschild concocted a scheme whereby the Danish prince would get the money without knowing who it came from. He would therefore be bound by honor to repay the loan.

This was Rothschild’s breakthrough. Not only did the stunt earn him permanent letters of transit for him and his family, it also laid the groundwork for a continent-wide messenger service that would surpass those of all the kingdoms of Europe. This service was used widely for many decades to come, since it was faster and more confidential than any other such service then in existence. What’s more, the confidentiality did not extend to the Rothschilds themselves; by reading the messages being sent via their service, the Rothschilds were finely attuned to the political and financial activities of all of Europe. This arrangement led eventually to the Rothschilds’ virtual takeover of the British stock market and, therefore, their ascension to European aristocracy.

Mayer Rothschild’s five sons went on to form the largest banking conglomerate in the world, with branches in London, Paris, Vienna, Naples and Frankfurt. Their immense wealth and influence deeply affected the political landscape for many decades. The Rothschild’s achievements include the building of the Suez Canal, the Cape Town to Cairo railway, the formations of Rhodesia and Israel, and the rise of the De Beers diamond concern, to name just a few. The Rothschild’s influence had diminished significantly by the 20th century. The rise of Hitler forced them out of Germany and Austria; the annexation of Naples by Italy brought a halt to the Naples branch of the bank; and the emergence of national banks in England and France greatly reduced their influence in those countries. But the Rothschilds’ effect on the contemporary political topography can still be deeply felt. The current Rothschild generation is active in philanthropy, the arts and politics. Their impact cannot be overstated.

Posted by creation of the nation at 8:44 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory

Friday, October 14, 2005

Temporary Insanity

Once again, the employment god has cast a critical eye in my direction. Without dwelling on the details, let’s just say that my most recent situation came to an acrimonious end. It wasn’t my fault — really. I didn’t mean to tell the boss his way of doing things was moronic; it just slipped out. In any event, my meager wages from that job left me little time with which to contemplate my next move. I had to act fast or I’d be spending the winter under a viaduct.

One of my previous swims in the treacherous waters of pre-employment dealt me an entanglement with a dangerous sea creature known as a temporary agency. The temporary agency is a creature with long, powerful tentacles with which it draws its prey into a deep, dark world of cubicles and 15-minute breaks and fast food lunches and unwanted friendships. The temp agency feeds primarily on desperation and aspiration, but will settle for a steady diet of petty recriminations. Its victims struggle eternally in a web of cute, inspirational banners and office birthday parties.

A favorite method of capture for the temp agency is to attach a tentacle to the victim and then just sort of forget about it. The would-be victim goes about its business unaware that it has a tentacle attached. In rare cases, the victim grows big and strong and the tentacle is unable to reel it in. The temp agency doesn’t care; it has many tentacles. But, more commonly, the victim goes about its business until some trouble arises and a struggle ensues. The struggle is an instantaneous signal to the temp agency, which quickly attaches more tentacles to both combatants. The scorned employer is suddenly in the market for fresh meat. The temp agency’s tentacles tighten. The unappreciated employee self-righteously but desperately seeks another source of income. The tentacles tighten.

Such was the case for me when I found myself — again — in the boiling and infested sea of hunger and overdue bills. The tentacle rescued me. It scooped me up and placed me gently on the warm beach of secure employment. It placed a refreshing drink in my hand, and, just as my lips were about to meet the straw, the tentacle jerked me violently into a deep miasma of pointless, demeaning servitude.

Some days are just unBEARable.

As I dressed myself for my first day of training, I noticed that my gut was even more difficult to tuck into my “good” pants than it had been at my previous job. Either I had been drinking more beer — and that can hardly be possible — or my metabolism is slowing with age and all that beer is growing more difficult to burn off. The previous night’s session was no consolation: I had to drink at least five beers just to find the courage to accept this dead-end position.

I arrived at my assignment at 8:30, but Kathleen Watson’s digital clock radio read 8:39. Kathleen Watson was the head of the company’s human resources department, which meant that she was the overseer of all the wage slaves. She didn’t look afraid to use the whip.

“May I help you?” she asked icily.

I quickly and timidly stated my business.

“Oh. Finally,” she said. Her short hair was red on the outside and black on the inside. Her tight dress revealed what was probably once a great body, but now it looked as though it had seen many miles of rough road, as they say. Her creased face and baritone voice betrayed years of smoking. I tried to imagine what brand of cigarettes she smoked. After a moment’s consideration, I concluded that she must smoke More’s — those long, dark brown, cigar-like coffin nails. She wore bright red rouge on her cheeks and crimson lip-gloss. Suddenly I pitied her.

“I’m sorry. Am I late?” I asked apologetically.

“You were supposed to be here at eight.”

“Oh. I was told 8:30,” I explained.

“Well, it’s eight thirty-nine,” she said sharply. Then she spirited away. I wasn’t sure if I should leave or stay. Had I missed the opportunity, such as it was? Suddenly, she returned with two pieces of paper.

“Sign here and here,” she commanded. I obeyed. “You can wait over there,” she said, gesturing crudely at a couple of chairs. I sat down and picked up a Newsweek that was resting on the end table. I flipped serendipitously to a story — a story, mind you, not an advertisement — about a $1.2 million special edition Mercedes Benz that will soon be available — sort of. The one pictured next to the article looked like something Johnny Quest would drive. It had a silverish aura around it. Mercedes, according to the article, plans to manufacture only 25 of the cars. It has a V-12 engine, gull wing doors, some kind of ceramic polymer body and an unfathomable top speed. In order to change a flat tire, the article said, owners must wait for a specially trained German mechanic to fly in from Mercedes headquarters in Bonn. Mercedes has already received 200 orders for the machine, which gets eight miles to the gallon.

Someone called my name. I looked up to find that a fat, blonde woman was, by all outward indications, extremely happy to see me.

“Hi!” she exclaimed. For a moment, I thought she recognized me from somewhere. I tried briefly to place her face in my resinated memory, but I quickly realized that I have met at least a million women just like her. Her manner of speaking turned everything into a one-word question.

“Firstthingwe’regonnado?” she began. “IstakeyerpitcherforyerIDbadge?”

“Okay,” I replied hesitantly.

“Okay!” she cheered. She shuffled hastily away, cradling a clipboard like a child on her ample hip. I inferred that I was supposed to follow her.

In a small room down a dark hall, someone had erected an enormous camera and tripod assembly. She nudged me into a chair and shoved my head against the wall. She then jerked my head to the side so that it lined up with a piece of tape on the wall.

“Okay!” she cheered again. She leapt behind the enormous howitzer of a camera and aimed a menacing flashbulb right at my face. A blast of pure white blinded me for several seconds.

“Okay! One more!” she exclaimed. The second shot, I figured, was meant to insure total blindness.

As I sightlessly groped my way, she led me through a maze of cubicles until, at last, we reached one occupied by another obese woman. This woman, who I could barely see, was going to be training me for the next few days. She, too, spoke in one-word questions.

“Himyname’sjenniferhowyadoin’?” she chirped. As my eyes recovered, I noticed a poster hanging on the wall of her cubicle. It was a photograph of a yawning grizzly bear. Along the bottom, in cheerful lettering, the caption read: “Some days are just unBEARable!”

“I’ll drink to that,” I thought.

After a while, with Jennifer yammering endlessly and me nodding in endless agreement, I became aware of several other posters decorating her cubicle. They had obviously been manufactured for fourth grade classrooms. One showed Charlie Brown and Peppermint Patty and the gang painting a big sign that read, “Everything goes better when we work together!” Another one had a photo of a gorilla that appeared to be smiling — wildlife is popular among cubicle dwellers — the caption read: “Smile! It’s the first thing people like about you!” Yet another poster showed a bald eagle in two views superimposed on one another. Its caption read: “Let your dreams take flight!”

Obviously, exclamation points are the only punctuation employed by inspirational poster manufacturers.

The company to which I had been assigned on this go-around ran some sort of money order scam. It involved risky, short-term investments and probably resided somewhere right on the edge of legality. The place was loaded with surveillance cameras and signs that read “Access Restricted.” Everyone — even temps — had to wear an identification badge and security card. The card and the badge were attached to a retractable spool that could be clipped to a strap or belt.

On the second morning of my assignment, I was accosted near the front door by a security-conscious prick. (They’re everywhere these days.)

“Have you got your badge?” he demanded in a passive-aggressive sort of way. Now at this particular point in the day, a beige cubicle festooned with childish regalia was just about the last place on Earth I wanted to be. I should have said, “Nope. I’m an interloper. Kick me out.” But, instead, as you already know, I said, simply, “Yep,” as I obediently extended my ID badge. The frustrated Gestapo asshole reluctantly let me pass.

The training for my pathetic assignment consisted of two phases. The first was to learn how to load and operate the electronic money order dispensers used by the company in its scam. Since the rest of the operation relied on economic mumbo-jumbo and loopholes, mastery of the dispensers — the only tangible ingredient in this recipe for deceit — was required by everyone. The dispensers came in four models, from old and crappy to new and crappy. I had to learn the rudiments of their operation so that, when convenience store workers called me with questions about their machine, I would be able to walk them through the solution, step by step.

The second phase of training entailed learning how to read a variety of computer screens between which I would eventually be flipping. The screens provided the viewer with essential information about the money order machine in question. The convenience store worker would call to report — often in broken English — a malfunction of some sort with his or her money order machine, and the operator — me — would use the information on the screens to identify the problem, work on a solution and record the events of the call.

Due to lack of interest, I was the only person who showed up for training. This, said Jennifer, meant that training would go “way faster.” As we concluded each step of what I considered a mind-numbingly slow process, Jennifer would squeal with delight: “My! Ican’tbelievehowfastwe’regoing!”

Midway through the pea soup fog of my first morning, the first obese woman returned with my access card and identification badge. The badge was still warm from having been run through an electric laminating machine. The picture on my badge betrayed the feeling of dread that had been — and was still — coursing through every fiber of my being. No mention was made of the second picture. No doubt it has found its way into my Permanent Record.

Break time. At last. The only positive aspect of this particular work environment is the religious devotion its inhabitants have toward breaks. This is undoubtedly the result of countless migraines, acts of vandalism, unearned sicknesses and other forms of productivity-reducing defiance from the wage slaves. I walked to the lunchroom as quickly as I could without attracting attention. I poured myself a large cup of bad office coffee in a futile effort to fortify myself against the insanity that surrounded me. Coffee was the only mind-altering chemical permissible in this land of NFL memorabilia and United Way fundraisers, so I partook heavily. I sat down and completed a crossword that someone else had tried to fill in using a yellow felt-tip. The lead story in that day’s paper told of a local doctor who had punched a woman in the face. The woman, according to the story, had cut in front of the doctor in traffic. Naturally, the public’s sympathy was with the woman; naturally, mine was with the doctor.

Upon my return from break, I detected a commotion of some sort wending its way slowly through the cubicles. If it continued on its present course, the commotion would eventually arrive at my desk. I would be forced to interact. It wouldn’t be so bad if they would just let you work in silent hatred, but there is always some “Rah! Rah! Sisboombah!” bullshit taking place that is obviously designed to convert the nonbelievers. It’s like a Christian summer camp five days a week.

As the commotion in question made its way relentlessly toward me, it became clear to my non-believing eyes that it consisted of four grown men dressed as old ladies.

“What the fuck is that?” I demanded. In panic, I pursed my lips. Did I say that or just think it?

“Oh. It’stheMoneyGrams,” explained Jennifer gleefully. MoneyGram, she said, was one of the product services offered by the company. The company, she said, invented a character called a “MoneyGram,” which was really just a money-dispensing old lady, to promote this product service. Every month, in an effort to raise money for United Way, some of the employees would take part in a goofy stunt of some sort. On this particular occasion, some of the employees offered to pay an unspecified amount of money to United Way if these clowns would dress up as “MoneyGrams.” The poor slobs had to choose between paying the unspecified sum or dressing up as old ladies, in which case the challenger would be compelled to make the payment. I was doubly horrified. For starters, I had no desire to stand there and take part in this foolishness, and, secondly, I feared that the longer I worked there, the greater the chances that I would be forced to participate. But, by that time of course, I will have been thoroughly converted. It was all I could do to keep from running away.

After four days of this nonsense, I concluded that sleeping under a viaduct wasn’t that bad after all. When I went to the temp office to turn in my time sheets, I told my supervisor that I could no longer tolerate this position and that I wanted another assignment. She looked at me with that look that people give you when you tell them that you hate something that they love — blueberry pie or For Whom the Bell Tolls, for instance.

It was unfathomable to her that, in this economy, someone would choose not to leap at the chance to become part of the Great American Workforce. To her, I was one of “them;” I was one of the people who “chose” to eat out of dumpsters and guzzle cheap wine. Nothing I could say would illuminate the vast regions of voluntary ignorance that occupied her soul.All I could do is take a deep breath and wonder silently if I had enough money for a beer.

Posted by creation of the nation at 7:58 PM 0 comments

Labels: Losers, rancorous humor, Trickle Up Theory, work

Tuesday, October 11, 2005

The Trickle-Up Theory (part 1)

How Banks Prey on the Poor

When I was about eight years old, I opened my first bank account. It was a passbook savings account, and I’ll never forget the smiles on the bank managers’ faces as they patiently helped me fill in all the necessary paperwork. At the time, I assumed the smiles were inspired by the cute novelty of a little boy opening his first account, but upon reflection, I realize they were smiling at me the way Dracula smiles at his next victim.

“Come hither,” they beckoned helpfully. “I think you’ve got something on your neck.”

That experience 30 years ago was my last pleasant banking transaction. Since then, my banking career has been a nightmare of hidden fees, overdraft charges, denied loan applications and collection agents. Banks refer to their victims as customers, but a customer is someone whose repeat business one is trying to earn. Banks act as if they are doing you a favor by allowing you to open an account.

I have a friend who refuses to open a bank account. He keeps his money in a cookie jar on the top shelf of his cupboard. When he gets the desire to buy something like a new computer or a stereo, he simply saves his cash in the cookie jar until there’s enough to make the purchase in question. He pays his rent in cash; he buys money orders for his utility bills and all other expenses for which cash is inappropriate.

I used to make fun of him for his lowbrow approach to finance. Many times I derisively told him of the old Lithuanians I saw while waiting in line at my bank in Chicago who would come in every Saturday to count their money. The bank tellers wore expressions of frustrated resignation as the distrustful oldsters would demand to see their money and count it. I laughed cruelly at the way the old guys never realized that it was the same $5 thousand being counted over and over.

But who’s laughing now? As I write this, my checking account is overdrawn by $149.00. Every day it’s in the red, they add another $5.00. Are they doing this to earn my repeat business?

Those old Lithuanians are right to distrust banks. And so is my friend. Here’s why:

There are several methods banks use to extract as much money from their customers as possible. I should say from their poor customers, because the true purpose of almost every bank is to serve the rich at the expense of the poor. According to the New York Times, banks received over $30 billion in overdraft fees in 2001. Rather than offering overdraft protection to the working poor at a reasonable interest rate of, say, 10 to 20 percent, depending on the customer’s credit worthiness and length of employment, banks instead agree to cover bounced checks and debit card transactions and charge a fee of $20.00 to $35.00 for each overdraft. That means the $2.00 cup of coffee you purchase using your debit card two days before payday could end up costing you $37.00 or more. In effect, the bank is offering you a loan at an interest rate of around 190 percent. If you tack on the $5.00 or more per day many banks charge overdrawn accounts, the percentage rate climbs to over one thousand percent. That had better be one damn good cup of coffee.

But that’s not all. Most banks use many shady tricks to maximize the possibility of your being overdrawn. Here’s one little trick banks use to exploit their working class clientele:

Let’s say you have written several checks this week. The first check was for $650 for your rent or mortgage payment. The second check was for $45 for your phone bill. The next two checks were for around $20 apiece for gas and electric service. Then another one for around $40 or $50 for groceries. Then, throughout the week, you wrote three or four more checks for between $5 and $10 apiece for lunch. On top of that, you stopped for coffee a couple times on your way to work and wrote checks for around $2 each time. Throw in a pack of smokes or a six-pack of beer here and there and by payday, you’ve overdrawn your account by $15 or $20. Well, rather than debiting all the small checks first and then charging the $35 overdraft fee for the $650 rent payment, they debit the largest checks first so that they can charge the $35 overdraft fee several times over on all the little checks. Don’t believe me? Check your bank statement at the end of the month.

What’s more, most banks increase the overdraft charge if you’ve had more than a certain number of overdrafts in a given period of time. If you’re like me, the first pay period of the month can be difficult because rent and most utility bills are due by the 5th of the month. The obvious solution is to apply for overdraft protection. Overdraft protection provides the customer with a line of credit that kicks in automatically when expenditures exceed the amount of money in the customer’s account. The loan is paid back usually at an interest rate similar to that of most credit cards.

Unfortunately, the bank customers who need this service the worst – ones who find themselves in the red about once per month – are the ones least likely to be approved for such protection because they are considered bad credit risks. Paradoxically, one of the things the bank looks at in considering customers for overdraft protection is how many overdrafts the customer has had within the last 18 months or so. When my application for overdraft protection was denied for this very reason, I decided to create my own overdraft protection. My current financial tormenter, U.S. Bank, offers a service called a “goal savings account.” This service automatically transfers a certain amount of money – in my case, $25 – from my checking account into my savings account once per month. Since they would not approve me for overdraft protection, I asked them if they would set up my accounts such that if I overdrew my checking account, the needed sum would be transferred automatically from my “goal savings account.” They gladly agreed. What they failed to mention, however, is that each time such a transfer occurs, my account is charged $5. So, if I have $2 in my checking account and I write a check for $5, it will cost me $5 to transfer $3 from my “goal savings account” to my checking account. Their failure to notify me of the $5 charge resulted in both my accounts being overdrawn.

In effect, U.S. Bank – like all banks I’ve encountered – is like a shark, no wait, a vulture, pouncing on the animal in distress and regurgitating the digested flesh into the waiting mouths of the rich who sit uselessly squawking in the nest. Or something like that.

When you take all this into consideration, the word “customer” takes on tragicomic dimensions. What if a tailor treated his customers the way banks treat theirs? If he knew you were poor, he would sew the buttons onto your shirts in a way that guaranteed they would pop off the second or third washing and then charge you to replace them and increase the replacement charge by 10 percent every fifth button. He would simultaneously do exquisite work for his rich customers while giving them deep discounts and free alterations and repairs. Plus, he would be rude and dismissive every time you entered his shop. Come to think of it, this is precisely what tailors do, only they’re not tailors any more, they’re The Gap.

To add insult to injury, the advertising campaigns for most banks are patently dishonest. TCF Bank in Minnesota claims in their ads to offer “totally free checking,” while First Bank in Kansas tells its customers to “relax…you deserve consideration.” This advertising approach gives prospective customers the false impression that if, like roughly 3 million Americans, they are living paycheck to paycheck and find themselves in financial difficulty from time to time, they can count on the bank to help them out. This is a reasonable assumption. Why else, after all, would someone choose to keep his or her money in a bank?

There are three reasons that I can think of. First, banks are insured. If the bank is robbed or destroyed in a fire or tornado or some such calamity, the customers’ money remains safe and sound, whereas if my friend’s cookie jar is stolen or destroyed, he’s shit outta luck. Second, customers can earn interest on their deposit, albeit a tiny percentage. The third and most compelling reason someone might want to keep his or her money in a bank is Purchasing Power. If, like many Americans, you find yourself a little light towards the end of the pay period, you can simply “relax” because “you deserve consideration.” This relaxation, though, comes at a very high price. And the poorer you are, the higher the price.

Another scheme employed by many banks is a system of bizarre and constantly changing rules regarding when deposits and account transfers are posted. If, for instance, you make the deposit in person at a teller, it posts at one time, but if you make the deposit at an ATM, it posts at a different time. Many banks offer a 24-hour telephone line that customers can call to check their account balance, but this, too, is a ruse. On more than one occasion, I have called the number and made a purchase based on the balance information provided only to incur an overdraft charge because some previous purchase or debit was not yet reflected in the amount stated.

The American Heritage Dictionary defines customer simply as “one who buys goods or services,” but the American banking system has its own definition: “One who pays a lot for services, but receives only punishment.”

There is a tiny ray of hope, however, for the working poor who prefer not to keep their money in a cookie jar. It’s called the Credit Union.

Credit Unions are non-profit (if there is such a thing) banking institutions that, for the most part, act in the best interests of their customers. The idea behind credit unions is that, as with all unions, individuals obtain more power and autonomy when they work together.

The first credit unions were closely associated with labor unions. Teachers or plumbers or carpenters or journalists would pool their financial resources to provide low interest loans to the union’s neediest members, thereby providing assistance to working families who had been forsaken by traditional banks. The problem was that in order for credit unions to retain their non-profit, tax-exempt status, membership was required to be restricted to particular groups, such as trade unions or farmers or very small geographical areas such as townships or counties.

The Credit Union Membership Act of 1998 changed all that. This act allowed credit unions to significantly expand their eligibility without endangering their non-profit, tax exempt status. As a result, credit union membership has grown from about 64 million members in 1992 to almost 83 million members in 2002. And according to the Christian Science Monitor, Credit union-issued loans increased from a 16.1 percent share of the national market in 1992 to 17.1 percent in 2002.

Of course, traditional banks are pissed off about this development. And why shouldn’t they be? The $30 billion-per-year overdraft cash cow upon which they’ve been feeding is walking out the door.

“Once, members of a credit union knew each other and pooled their resources to provide credit for their co-workers and neighbors,” laments the American Banking Association web site. Today, the diatribe continues, credit unions can serve entire states. “Despite this departure from their original mission, these credit unions continue to be afforded special treatment, including exemption from federal taxation and from the regulatory responsibilities that apply to commercial banks.”

Well, boo hoo. Congress has acted on behalf of its constituents, for a change. Whatever will those poor, mistreated banks do now? I guess they’ll just have to take their $30 billion bat and ball and go home. When will these insouciant greed heads ever learn? Had they treated their working class customers with respect when they had the chance, they wouldn’t be witnessing this exodus into credit unions today.

But this doesn’t mean things are all peaches and cream for working class Americans. Credit unions still require a credit application to qualify for loans and overdraft protection, and with many such customers emerging bruised and battered from commercial banking’s rapaciousness, credit histories unfairly reflect poor ratings.

to be coninued

Posted by creation of the nation at 8:21 PM 0 comments

Labels: accounting, Trickle Up Theory